- Home

- >

- Plants have teeth

Plants do not have teeth as they are not capable of movement. However, some plants have developed defense mechanisms such as thorns to protect themselves from predators. Plants belonging to the Urticaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Loasaceae, and Hydrophyllaceae families have evolved to grow thorns as a proactive defense strategy. These thorns can cause pain or irritation when touched or pricked by them. The discomfort caused by these thorns may deter animals or humans from attempting to touch or consume these plants. For example, the plants of the Loasaceae family, found in America and Africa, can cause intense pain when touched. The reason behind the pain caused by these thorns is due to their structure and the chemical compounds they contain.

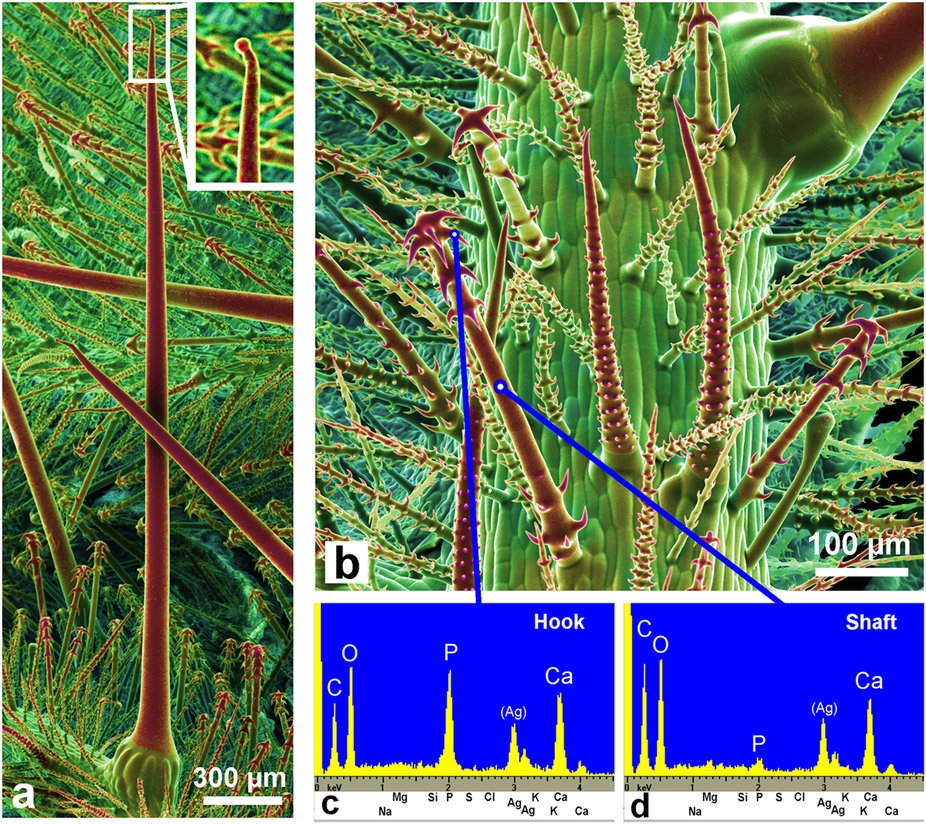

Let’s first take a look at the dlectron microscopy images of thorns provided by a research team from Germany:

-

It turns out that in addition to the small trichomes we commonly associate with thorns (as shown in Figure b), these plants also have "stinging hairs" (as shown in Figure a). Stinging hairs are single-celled structures with a spherical tail at their tips. When they encounter mechanical pressure, such as being touched or bitten, the tail will detach. Once detached, the hollow cavity inside the stinging hair injects the toxic fluid from the plant's cells into our skin, similar to subcutaneous injection. This fluid contains substances such as histamine, acetylcholine, serotonin, and other unidentified compounds, which can cause extremely painful reactions. On the other hand, although small trichomes cannot inject venom, they are densely distributed all over the plant (as if they weren't small enough!). The combination of stinging hairs and small trichomes creates an excruciating experience when we get pricked.

Perhaps it is this intense pain that sparked the interest of the German research team, leading them to study the structure of the stinging hairs and small trichomes of plants in this genus. Surprisingly, they found that thistles from the Loasaceae family, in addition to having venomous stinging hairs and small trichomes, have their tip regions of the stinging hairs and the fine thorns of small trichomes composed of hydroxyapatite [2]. What's special about hydroxyapatite? Other plants with thorns usually strengthen them with calcium carbonate or silica, while thistles from the Loasaceae family use hydroxyapatite. Hydroxyapatite is the component of mammalian teeth and bones, and it has never been observed in any structure of plants before. Conversely, stinging hairs of plants from the Urticaceae family, which also possess stinging hairs, only contain calcium carbonate and silica, but this does not diminish their lethality. For example, the stinging tree (Dendrocnide moroides) from the Urticaceae family is the most poisonous thorny plant in Australia and has been known to cause death in horses.

This discovery has left the research team curious. Why do plants from the Loasaceae family use hydroxyapatite to strengthen the tips of their stinging hairs? Could it be that they are unable to metabolize silica or calcium carbonate? This question was quickly answered when the research team found crystals of calcium carbonate and silica next to the hydroxyapatite in the stinging hairs, proving that they have no trouble utilizing calcium carbonate and silica.

So why do plants from the Loasaceae family use hydroxyapatite? It remains unclear at this point. However, this is the only known example in higher plants where hydroxyapatite is utilized. Since these thorns are typically designed to deter herbivores from grazing on them, one could say that it is a form of "an eye for an eye" defense mechanism. Nonetheless, the presence of stinging hairs that inject venom and small trichomes that resemble wolf's teeth is truly hair-raising.

References:

[1] E. Laurence Thurston, Nels R. Lersten. The morphology and toxicology of plant stinging hairs. The Botanical Review. 1969, Volume 35, Issue 4, pp 393-412

[2] Hans-Jurgen Ensikat et. al., 2016. A first report of hydroxylated apatite as structural biomineral in Loasaceae – plants’ teeth against herbivores. Scientific Reports. doi: 10.1038/srep26073

Author: Yeh, Lu-Shu

Assistant Professor, Department of Life Sciences, Tzu Chi University. Science writer specialized in popular science articles.